We're less than a week out from the 100th running of the Hakone Ekiden, the two-day university men's road relay from central Tokyo to the foothills of Mt. Fuji and back that has become the biggest sports event in Japan. Tens of millions of people watch the live TV broadcast, millions more line the 217.1 km course, it has its own museum, and its own identity and place as a cultural icon. Over the next few days I'll be posting four excerpts from my upcoming book on the history of the race, May the Circle Be Unbroken: Hakone at 100.

The Hakone Ekiden came out of the same era that produced the world's other premier endurance races, specifically the Boston Marathon, Tour de France and Comrades Marathon. Comrades didn't come until a bit later in 1921, but Boston was first held in 1897, and six years later in 1903 the Tour de France got off the ground. In Japan Meiji University founded the Meiji University Race Club, the country's first collegiate track and field team, in 1907, a step toward what came next.

Hakone's roots date to the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, where Japan sent a team for the first time. That team consisted of two athletes, sprinter Yahiko Mishima and marathoner Shizo Kanakuri. Kanakuri was energized by the experience and, in the context of Japan's international ambitions in that period, saw the Olympic movement as a gateway to Japan becoming a more important part of the global community. When he returned to Japan he actively proselytized and worked to expand opportunities for development in athletics and in particular his distance, the marathon. Among his many contributions was the event that came to be called the Hakone Ekiden.

Inspired by the first ekiden held in 1917 to commemorate the move of the nation's capital to Tokyo, Kanakuri conceived of an event that would focus on roughly the half marathon distance as a way of developing the next generation of marathoners and identifying those with Olympic potential. From its start in 1920 the basic format was set: Tokyo-area university teams of ten running in relay, with five runners covering the 100 km+ distance from central Tokyo to the mountain town of Hakone, and five more handling the return trip the next day.

1920s

In that first edition on Feb. 14-15, 1920, four schools from the Tokyo-centric Kanto Region lined up for the "Four Major University Ekiden Relay," Tokyo Koto Shihan Gakko where Kanakuri worked, Meiji University, Waseda University and Keio University. Meiji led almost the entire way, but on the final stage Tokyo Koto's Zensaku Mogi came from 11 minutes behind to run down Meiji's anchor and win by 25 seconds. Later that year Mogi and Yahei Miura, who handled the 800 m+ uphill Fifth Stage for Waseda in the first edition, joined Kanakuri and another runner, Kenzo Yashima, as part of Japan's marathon team at the Antwerp Olympics, and the new relay's position in Japanese marathon development was established.

Attracted by print media hype, the excited public reaction and the connection with Kanakuri, in its 2nd edition on Jan. 8-9, 1921, three more schools, Tokyo Nogyo University, Hosei University and Chuo University joined the field, with another three including Nihon University joining for the 3rd running in 1922. In the 1923 race the Olympian Yashima joined Meiji as a 1st-year, breaking the Third Stage course record, the anchor stage CR as a 2nd-year, and winning the uphill Fifth Stage as a 3rd-year to help lead Meiji to back-to-back wins. His 4th year he broke the Fifth Stage record too, and, in what was not unusual at the time, returned for 5th and 6th years with another Fifth Stage win and helping Meiji score another overall win his 6th year in 1928.

No other runner dominated Hakone's early years like Yashima, but for the most part the original four teams continued to take the top spots. It took until the 7th running in 1926 for a school outside the original four, Chuo, to take the win. Running the 1928 Hakone for Kansai University at a time when the door was open for teams from outside Kanto, Seiichiro Tsuda broke Yashima's Fifth Stage record, and later that year he became the first Hakone runner to make an impact at the Olympics, taking 6th in the marathon at the Amsterdam Olympics.

1930s

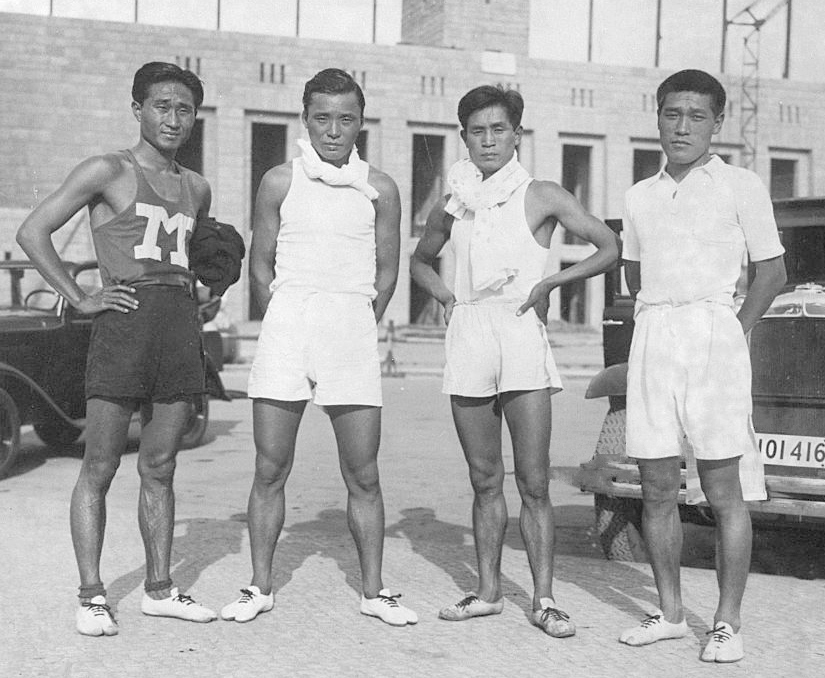

Transferring to Keio, Tsuda took 2nd on the Fifth Stage at the 1931 Hakone, and a year later at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics was 5th in the marathon. Behind him, Koreans Kim Eunbae and Kwon Taeha were 6th and 9th in the Japanese uniform. Kwon was already at Meiji at that point, running Hakone every year from 1927 to 1932 and breaking the Fourth Stage record in 1928 and the Seventh Stage CR in 1931. Kim entered Waseda and likewise broke the Seventh Stage record in 1934.

But the dominant runner of the decade never went to the Olympics. In 1931 Hiroo Nanba made his Hakone debut with Hosei University, winning the Fourth Stage. Nanba then made the unusual move of transferring to Nihon Shikai Technical School, and running in their colors he returned in 1933 to break the Fourth Stage CR over five minutes faster than he'd run two years earlier. A year later he broke the Third Stage CR as well, and in his final appearance in 1935 won the Third Stage a second time.

Powered by their Olympic marathoners, Meiji, Waseda and Keio continued to control the event, and a team outside the original four didn't win again until 1935 when Nihon University took the first of what became four-straight titles. By that time the field had grown to 13 teams, and for the rest of its history it remained in the double digits.

1935 saw Korean Nam Seungryong take a solid 2nd on the uphill Fifth Stage for Meiji, and a year he became the first, and still only, Hakone runner to win an Olympic medal when he took bronze at the 1936 Berlin Olympics under a Japanese name and uniform. Nam returned post-Olympics to win the Third Stage in 1937, and gold medalist Sohn Kee-chung joined him at Meiji. But for reasons not widely discussed, Sohn never lined up at Hakone.

In 1936 Tokyo was named host city of the 1940 Olympic Games, and the impact on motivation was immediate. In the first edition of Hakone Tokyo Koto had averaged 4:36.7/km for the full course. That was under 4:00/km by the 2nd running and quickly progressed. At the 1937 Hakone, the first after the Olympic news, Nihon became the first school to clear 3:10/km when it averaged 3:07.3/km. But as Japan's military activity in the Pacific grew and WWII approached, the availability of athletes became a problem and the overall average pace slowed. The Tokyo Olympics were canceled in 1938, and it would take another generation, until the 1964 Hakone Ekiden and another Tokyo Olympics just around the corner, for someone to better the 1937 Nihon University team.

1940s

The 21st running in 1940 saw Nihon take its sixth of six wins in seven years, interrupted only by Senshu University's 1939 victory, but with steadily increasing military activity the use of the roads along the ocean south of Tokyo that had become the race's established course was barred for the 1941 race. The Kanto Region Collegiate Sports Association, KGRR, now handling organizational duties came up with an alternate 8-stage, 107.0 km inland course between central Tokyo and Ome in the mountains west of the city. That race happened on Jan. 12, 1941 with Nihon again taking the top spot. The 2nd running on that course was bumped up from January, 1942 to Nov. 30, 1941, and again Nihon emerged on top. A week later the bombs fell on Pearl Harbor.

As World War II raged, on Jan. 5-6, 1943, a ten-leg university relay was held on a different course between Tokyo's Yasukuni Shrine and Hakone. With Yasukuni serving as a shrine to Japan's war dead the race was essentially morale-building propaganda to inspire victory. The war meant a shortage of young men; teams had to be padded out with sprinters, field athletes, and people from other sports, and there was turnover in the lead at almost every exchange. But despite this, Nihon won again. Although it was held under a different name, this race is counted as canon in the official Hakone Ekiden event history, while the two editions in 1941 are not. Much like the Boston Athletic Association counted a WWI-era 1918 military relay in Boston Marathon history, this muddies the water about what really constitutes the 100th running.

For pretty obvious reasons no race happened from 1944 through 1946, and when the Hakone Ekiden returned in 1947 it was open to any university that could field a full team. But even with people from other sports, the war's toll on the population of young men meant only ten teams started. Meiji won the first of a series of duels with Chuo, but the performance level had fallen back to where it had been at the end of the 1920s.

Japan was banned from the 1948 London Olympics, but three Korean athletes ran under their own flag for the first time. Among them was Suh Yan-bok, coached by Meiji alum and Berlin Olympics gold medalist Sohn.

1950s

Following Meiji's 1949 win it faded from the top tier, and throughout the post-war reconstruction and industrial development period it was a bitter rivalry between Chuo and Waseda, Chuo scoring six wins over the decade to Waseda's pair. At the forefront of Chuo's dominance was Shingo Nanmoku, only 8th on the Third Stage in his debut in 1949 but winning his leg every year from 1950 to 1953 including new CR on the Second Stage and Tenth Stage.

NHK Radio began broadcasting Hakone live with Nanmoku's final run in 1953, launching a new era of growth in the event's mass popularity. Chuo's win in 1955 marked the year that the race settled into what is now its traditional date of Jan. 2 and 3, a move made primarily to take advantage of roads being relatively empty due to people going home for the New Year holiday. The rebirth of Japan's industrial sector saw the founding of the National Corporate Federation of company-based running teams in 1957, creating an alternative organized pathway for runners at a time when university wasn't a realistic option for the working classes. This was to have a direct impact on the makeup of Japan's Olympic teams all the way up to the 1990s.

Nihon returned to the top in 1957 and 1958, then in 1959 Chuo began the greatest winning streak in Hakone history, taking six-straight titles that culminated with Hakone's 40th edition in the same year Tokyo hosted the Olympics for the first time.

1960s

The lead-up to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics saw the same kind of rapid progress in performance level as before the aborted 1940 Olympics, and in the final win of its six-year streak Chuo averaged 3:06.0/km for the entire Hakone course, the post-war generation finally breaking through the level set by Nihon back in 1938. But the final team named to the Tokyo Olympics marathon was made up of runners who had never run Hakone, a setback for Kanakuri's original vision almost 50 years earlier.

1965 saw a formalization of the field size at fifteen teams, and Nihon came back to claim the title of fastest team ever, averaging 3:05.2/km. 1st-year Kazuo Tsuchiya won the Second Stage to play an important role in that win, and with anchor stage wins the next three years, two of them new course records, and three overall team titles he played the biggest role of any individual Hakone runner of the 1960s.

But 1966 marked a shift in the landscape as teams outside those that had taken part in Hakone's first three runnings began to dominate, an indication of the rapid growth in Japan's population and economic growth post-war. Including the two Tokyo-Ome races in 1941, the old-school powers won 42 of the first 43 races. In the next 43 they won only seven. Juntendo University marked that change with its first win in 1966, shattering Nihon's record with a 3:02.3/km average pace that wasn't bettered until 2011, and three years later Nittai University exploded onto the scene with its first win in 1969.

1970s

1970 saw the launch of November's National University Ekiden, giving universities outside Kanto something to aim for. Nittai dominated Hakone through the first half of the 1970s with five-straight wins and six total over the decade. Yoshitaka Ishikura played a large role in the 1970-1973 wins, with three stage wins and a 2nd place his 2nd year. In Hakone's 50th running in 1974 Daito Bunka University 1st-year Hatsuo Okubo won the uphill Fifth Stage, going on to win it all four years and breaking the course record his 2nd and 4th years. With the most dominant Hakone runner of the decade in its arsenal Daito Bunka took its first win Okubo's 2nd year in 1975 and repeated the following year.

Then-future marathoner Toshihiko Seko's time at Waseda during the late 70s is remembered through a rose-colored rear-view mirror as one of the great eras of Hakone. A high school star who had failed Waseda's entrance exam the first year he tried to get in, Seko was unremarkable in his Hakone debut and only passably good his 2nd year. But when he broke the Second Stage CR his 3rd year in 1979 it was in front of the cameras for Hakone's first live broadcast on TV Tokyo.

That and his follow-up Second Stage CR in 1980 solidified his image in the public consciousness as a Hakone legend despite never contributing to a Waseda victory. Seko did go on to bigger things that neither Okubo nor Nishikura achieved, but both of them had a bigger impact at Hakone itself. The absence of TV cameras there to show the public and the contrast in attention and name value when Seko had them was a foreshadow of what lay ahead in Hakone's future.

1980s

Juntendo was the biggest power of the 1980s, winning a pair of titles in 1981 and 1982 and four-straight from 1986 to 1989 driven in part by Kazuhito Yamada, who outshone Nittai's future marathon world champion Hiromi Taniguchi as that decade's most dominant Hakone runner. Waseda did pull off back-to-back titles in 1984 and 1985, but after that it became a rarity for the traditional powers to take the top spot.

In 1987 the Hakone Ekiden broadcaster changed to Nippon TV, a move that was to have a decades-long impact on the race's popularity, its appeal to younger athletes, and the event's performance level, an impact that continues to deepen even today. 1989, the end of Juntendo's four-year streak, saw two significant developments. For one, the Izumo Ekiden launched in October as the opener of the three-race season that exists today.

For the other, rural Yamanashi Gakuin University did something that proved to be era-changing. Its roster that year included two 1st-year students from Kenya, Joseph Otwori and Kennedy Manyisa Isena. The first-ever athlete from outside Asia to run Hakone, Otwori won its most competitive stage by more than two minutes over future Olympic marathoner Kenjiro Jitsui of Daito Bunka. But Yamanashi Gakuin was only 7th overall.

1990s

It took until the Kenyan duo's senior year in 1992 for Yamanashi Gakuin to win outright, thanks in large part to Otwori taking 2nd on the Second Stage and Manyisa backing him with a CR win on the Third Stage. Yamanashi Gakuin won again in 1994 and 1995 on the shoulders of Stephen Mayaka, now a Japanese citizen and head coach at Obirin University, but although it has become a standard approach for developing programs to recruit Kenyans or Ethiopians to help them find their feet, even old-school power Nihon University getting into the act, no other team with an African athlete has ever won Hakone in the years since.

The World Championships were held in Tokyo for the first time in 1991, and Nittai's Taniguchi did the next-best thing to achieving Kanakuri's dream, winning the gold medal there. The first Olympics of the decade saw the resolution of events from over 50 years earlier. Coached by Meiji alum and Berlin Olympics gold medalist Sohn, Korea's Hwang Young-Cho beat Taniguchi and non-Hakone runners Koichi Morishita and Takeyuki Nakayama to win the gold medal at the Barcelona Olympics.

Back at Hakone, Daito Bunka became the first school to score the triple crown, winning Izumo, Nationals and Hakone in the 1990-1991 season. Both Waseda and Chuo scored rare Hakone wins, in Chuo's case its first since before the Tokyo Olympics in 1964. Waseda was driven primarily by the talented Ryuji Takei, who scored three CRs in four stage wins and the overall team title in 1993. 1997 and 1998 saw Kanagawa University, alma mater of current marathon national record holder Kengo Suzuki, emerge at the top for the first and second time.

2000s

With the turning over of the calendar in 2000, Komazawa University ran the fastest pace of any team since 1978, 3:03.9/km, to win the first of its eight titles to date. From 2002-2005 it backed that up with four straight wins, quickly establishing it as one of the dominant names in Hakone history. 2003 saw the field size expanded to 20, and the last year of Komazawa's four-year streak marked the beginning of Hakone's modern era of mass popularity.

Starting the final leg of day one, a tough climb with over 800 m elevation gain mostly in its middle 10 km, in 15th, unheralded Juntendo 2nd-year Masato Imai ran a still-inspiring CR-breaking run to put Juntendo into 4th. Sometimes you see someone do something that elevates us all, and this was that. It electrified the TV audience and turned Imai and the Juntendo team into national names, earning Imai the nickname "God of the Mountain." Imai came back his 3rd and 4th years to win the Fifth Stage in CR time again, and while Asia University snagged the win his 3rd year in 2006, he and his teammates came through for the overall win in 2007.

If Okubo had had the same kind of pre-Seko TV coverage he'd surely be remembered in the same breath, but with the TV audience growing every year and the spread of social media connecting fans in new ways and driving Hakone's popularity even further, 2009 saw the arrival of another icon. Toyo University 1st-year Ryuji Kashiwabara calmly told media pre-race that he was going to break Imai's Fifth Stage record. Which he then did, by almost a minute. Toyo won Hakone for the first time, and the excitement and hype around Kashiwabara surpassing Imai so quickly and the likable underdog Toyo team making it to the top was like nothing else in Hakone history.

2010s

The hype around him was so strong that it started to affect Kashiwabara personally. His 3rd year in 2011 Toyo was beaten by Waseda, who pulled off becoming the only team ever to break the CR at Izumo, Nationals and Hakone in a single season. But his senior year Kashiwabara won the Fifth Stage for the fourth year in a row, and with an average of 2:59.4/km Toyo was the first team in Hakone history to average under 3:00/km for the entire 217.9-km course. No runner since has matched Kashiwabara, and there's a case to be made that in all of Hakone history only Meiji's Yashima in the 1920s had a bigger impact.

The September, 2013 awarding of the 2020 Olympic Games to Tokyo had the same kind of effect on athletes' motivation as with the 1940 and 1964 Olympics. Performances across teams surged, and the seemingly untouchable sub-3:00/km pace Toyo had first achieved in 2012 was duplicated in 2014, 2015 and 2016 by both Toyo and another dynastic power to arrive on the scene, Aoyama Gakuin University.

Aoyama Gakuin had first run in the 1943 quasi-Hakone, and in 1976 its Hakone had ended with a DNF on the anchor stage. It didn't reappear until 2009 under new head coach Susumu Hara, when it finished last. But within six years Hara had developed it into a winning program, taking every year from 2015 to 2018 and pulling off the triple crown in 2017. Tokai University scored the 2019 title, its first-ever win, to break up Aoyama Gakuin's streak.

2020s

With the supershoe era in full swing 2020 saw Aoyama Gakuin on top again with a CR for the win, 2nd-place Tokai also under the old CR, and new CR on seven of Hakone's ten stages. Among those, Tokyo Kokusai University 1st-year Vincent Yegon turned in the greatest single run in Hakone history, a 59:25 CR for the 21.4 km Third Stage, 58:35 half marathon pace, enough to have TV commentators openly wondering whether the clocks were wrong. That wasn't enough for the KGRR to name him MVP, but after breaking the Second Stage CR the next year Yegon became the first non-Japanese runner ever to earn the award. His 4th year in 2023 he was named again after breaking the Fourth Stage record.

As the COVID-19 pandemic took off and events worldwide including Boston, Comrades and the Tour de France were canceled or postponed it wasn't clear whether there would be a 2021 Hakone Ekiden. But organizers enlisted the public's love for the event in asking them to stay home and watch it on TV as a condition of the race happening at all, and for the most part people did. They were rewarded with one of the most dramatic upsets since the first running in 1920, with Komazawa anchor Takuma Ishikawa running down Soka University's Yuki Onodera with 2 km to go, shutting down Soka's attempt at its first-ever win.

Aoyama Gakuin was back for a CR win in 2022. In the 2022-23 season Komazawa achieved the triple crown, one of the few things head coach Hiroaki Oyagi hadn't accomplished in his career with the team. Post-race he made the surprise announcement that he was stepping down to let former marathon NR holder Atsushi Fujita take the head coach's position, although he would remain as an advisor for the 2023-24 season. Under Fujita Komazawa won at Izumo and Nationals, meaning Komazawa goes into the 100th running set to do what no other team ever has and defend its title at all three, the double triple. In the biggest edition of the biggest road race the world has ever seen, it would be one of its biggest achievements.

Beyond

After running the Stockholm Olympics almost 112 years ago, sprinter Yahiko Mishima more or less accurately evaluated that it would take about a century for Japanese sprinting to be relevant. Marathoner Shizo Kanakuri immediately set about trying to build a development system for younger marathoners, and that has led directly to where Japanese marathoning is now, a solid 3rd in the world behind Kenya and Ethiopia. If he had been a miler and devoted the same energy and work to building a development infrastructure it's pretty reasonable to think the landscape now would look very different.

How successful was his idea of making a collegiate relay focusing on the half marathon as a way of cultivating international-level marathoners? If you go by the single criterion of Olympic medals, it has been almost a total failure. Only one Hakone runner has ever medaled in the marathon, and he wasn't even Japanese. But whatever the relative responsibilities of Hakone as a development system versus the corporate leagues as the ones actually training the marathoners, there's no denying that it now plays exactly the role Kanakuri envisioned. From the 2008 Beijing Olympics on, every male Japanese Olympic marathoner has had Hakone experience. The three men on the 2021 Tokyo Olympic team and the alternate were all Hakone stage winners.

And look beyond that. One of the greatest things about Nippon TV's broadcast is that every single runner gets featured on the broadcast. Every single one of them is mentioned by name. Most of them won't keep running after college. Most of those who do won't ever make an Olympic team. For most of them, Hakone is their Olympics. They live and breathe it every day for years, and if they are one of the lucky ones they get their chance, maybe two, maybe three, maybe even four, to have their day in the sun. A chance to shine in front of tens of millions of adoring fans. It's something they can carry with them the rest of their lives. And that's a beautiful thing.

The fans too can walk away with memories and inspiration that last forever. For all the talk about how to make athletics a bigger draw to mass audiences, it's obvious that with the Hakone Ekiden Japan cracked the code. The Boston Marathon, the Tour de France, and the Comrades Marathon have all become international icons. You could argue that the Hakone Ekiden has the same potential, and you could argue that a range of factors would prevent that from ever happening. But as it turns 100 the Hakone Ekiden stands alone, for good or bad, as the Holy Grail of the sport, as a major achievement of world culture, as the world's greatest road race.

Comments